Project

Data Driven Athlete (Student Athletes 1)

Project Description

How can data driven insights from digital twins empower Paralympians to find and maintain balance?

A digital twin is a virtual representation of an object, a person or a process. Creating digital twins requires accumulating and analysing large sets of data. They provide a model that can help predict future behaviour. It is this technology that we will explore in our design challenge.

Being a Paralympian means more than being the best at a sport. It means juggling sport, work/study, and living daily life with a disability. In this project, we paired up with the Hogeschool van Amsterdam’s Elite Sport & Study program and Streamingbuzz/Aionsports, an AR, VR, and streaming technology solution provider.

In this project, we explore the questions:

- How to make AR/VR/streaming technology more personalized, inclusive, and accessible?

- When, where, and how to deliver insights to enable balance?

- What unique insights do different types of stakeholders want/need? e.g. athlete, coaches, etc.

- What data to collect and how to collect?

- How to translate data into relevant insights?

This project focuses on the Sustainable Development Goals:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Our Progress

Maker’s Sprint

See the conversational object that was the result of our Maker’s Sprint.

We explored the question of making data visualisations accessible to visually impaired people. While our initial solution was to create a tangible 3D-printed graph, we opted do experiment more with the digital. As a result, we created a Multi-Sensory Data Presentation of our emotional states and their intensity throughout the week, which would allow to experience data both visually and audibly. Read more about our process here in our Medium post.

Research

During this Sprint we delved deeper into the research of our design challenge, users and technologies. To guide this process, we posed the following question as our Sprint Goal:

How could we use the Digital Twin technology to help student athletes reach well-being/balance throughout their daily life in an inclusive way?

To find the answer to this question, we took several directions of research.

First, in order to empathise more with the pains and challenges of our target audience, we conducted interviews with two Paralympic athletes from the Topsport Academie Amsterdam, as well as with the organisation’s manager. To get even more information on the matter, we investigated recent studies on the well-being and balance of student athletes. The main takeaway for us became the wide array of stressors and challenges that they encounter in their daily life, which differs them from just athletes or just students.

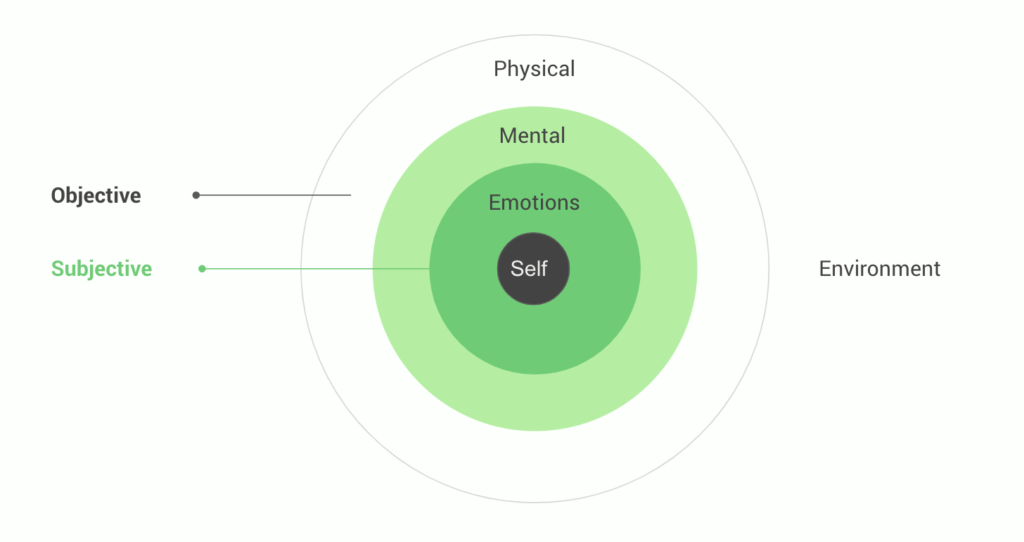

Second, our Sprint Goal motivated us to find a working definition of balance, that would guide us in future. However, after exploring the different views on the topic present in academia, we realised that balance is a multi-dimensional idea that couldn’t be narrowed down to either health, accomplishments in life or positive emotions. Instead, it represents a complex construct with subjective and objective layers.

This is the visualisation of balance that we came up with during our research.

Thirdly, a large segment of our research was devoted to technologies. Market research revealed that Digital Twins can be created by us either willingly, as in case with self-tracking applications, or without our awareness, as on the content-driven platforms like YouTube, Netflix and Spotify. The work of their recommendation algorithms mirrors our own tastes, beliefs and choices, so the content we see in our profiles can give a glimpse into what kind of Digital Twin these platforms have created for us.

To understand our partners’ technology, we went to visit StreamingBuzz for a discussion about the applications of their VR solutions. During this trip we had the chance to try out their VR experiences first-hand and learn more about their engine and development process. One important takeaway of this visit was the agreement to explore the audial aspects of the VR in our collaboration.

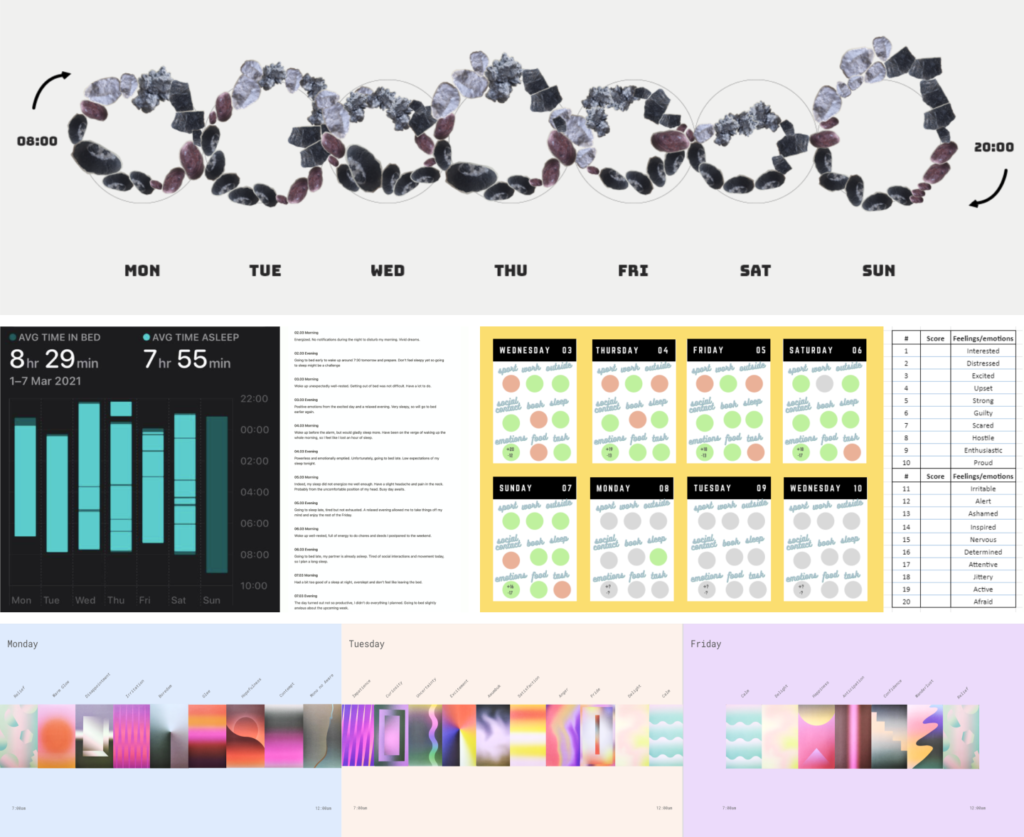

Lastly, as a part of our research on balance and well-being, we decided to explore our own notions of balance through a 1-week tracking experiment. Let alone to our own interpretations of this concept, everybody in our team opted for diverse techniques and resources that supported each of us individually, in our pursuit for balance.

Visualisations of our self-tracking research

From this experience, we’ve learned the importance of providing context and interpretation to data, the power of self-tracking in building better habits, and the endless possibilities of using self-tracking as an act of self-expression. Read more about the experiment and our takeaways in our Medium post.

If you would like to read more about our Sprint 1, read this more detailed post about our research and ideation. In the later post by Elisa, she shares some more in-depth findings of the research into the building of healthy habits and unconscious daily rituals we perform.

Ideation

For us, the ideation process spanned across Sprint 2 and 3. During this extended timeframe we conducted several internal brainstorm sessions, translate sessions with creative industry professionals and co-creation sessions with student athletes. By doing this, we were able to converge from over 10 concept direction to one unified vision.

Team brainstorms

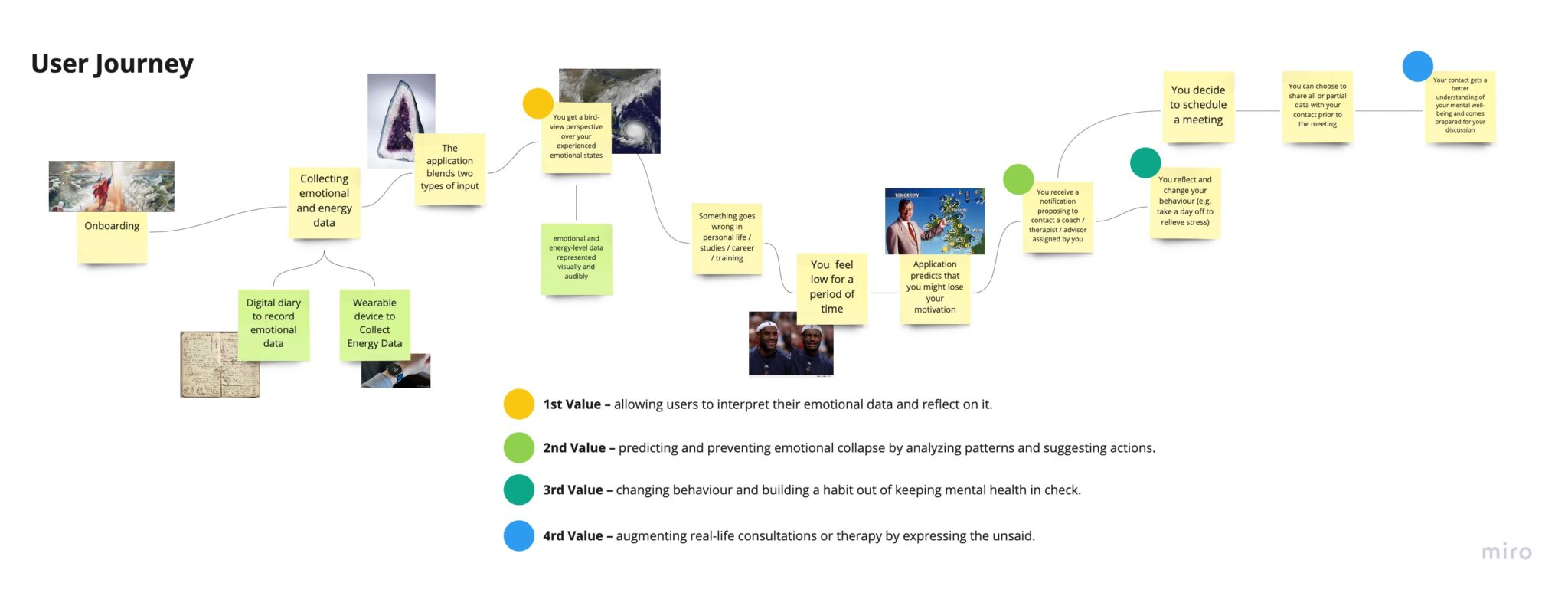

The purpose of our brainstorming was to revisit older findings and connect them to our fresher research. What helped us the most was dissecting our design challenge into separate concepts and identifying them, as well as re-listening to our older interviews. After accumulating so much information on the topics of balance, well-being, student athletes and accessibility, we had a different perspective on these materials. This allowed us to identify the main values to pursue with the solution, and to come up with the following User Flow map:

User journey and main values of our solution

Translate sessions with experts

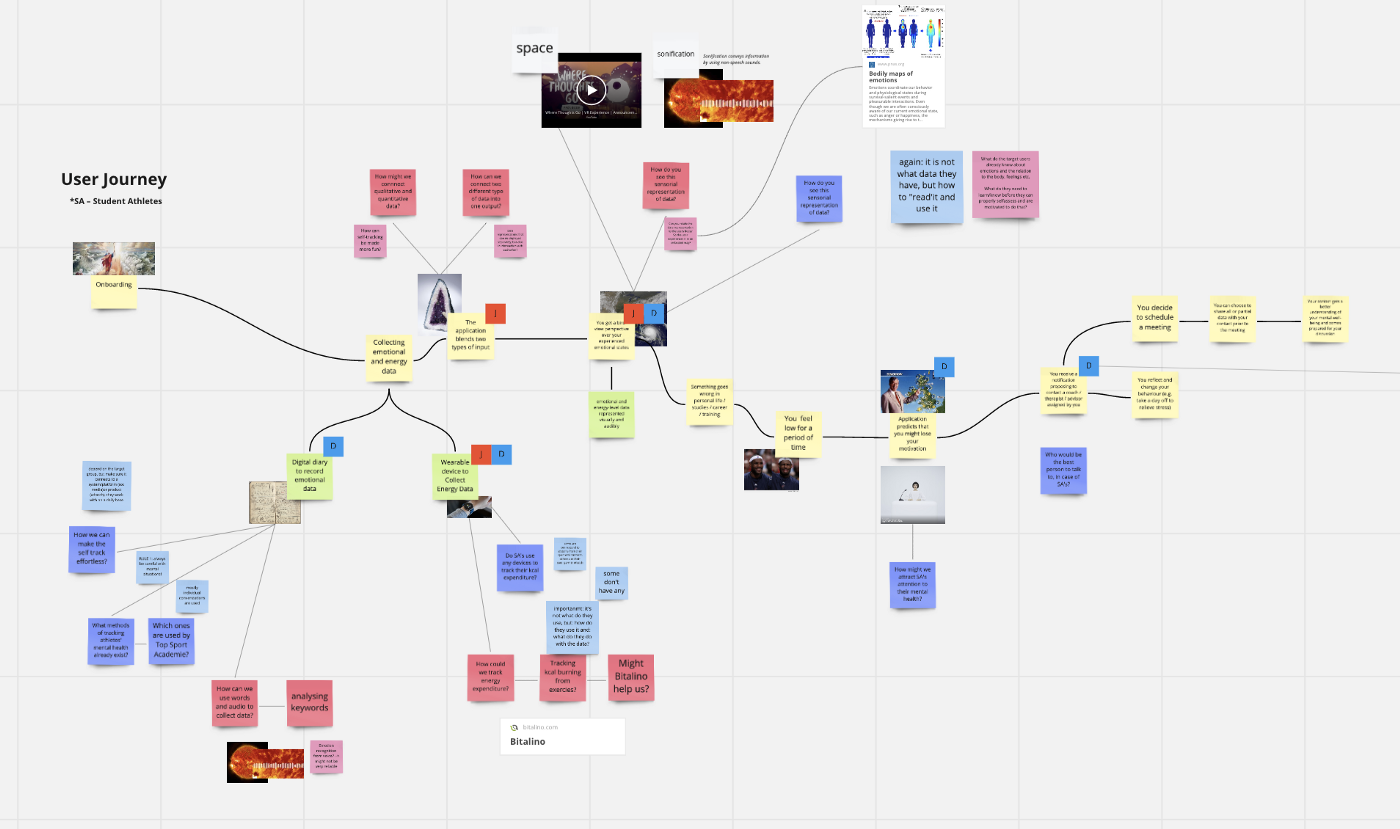

During the ideation phase we invited experts in design ethics (Dr. Charlie Mulholland from HvA’s faculty of Digital Media and Creative Indusrty), creative strategy (Marcel Schouwenaar from the Incredible Machine), student athletes’ motivation and performance (Dennis van Vlaanderen from the Top Sport Academie Amsterdam), and XR applications in the healthcare field (Jelger Kroese from Leiden University’s Centre for Innovation) to brainstorm on our challenges and to find answers to our questions. At DSS, we call these Translate Sessions.

The outcome of our ideation with guests

Co-creation sessions with users

However, we wouldn’t be human-centred designers, if we did not also maintain continuous contact with our actual final users. To learn more about the student athletes’ perception of their emotions, we conducted two co-creation sessions with ex- and current members of the Top Sport Academie. The student athletes took part in a week-long self-journaling experiment and shared their feedback during these sessions, generating insights about their habits and daily rituals, but also revealing what methods they already use to work with negative emotional states.

Therefore, while the translate sessions allowed us to turn assumptions into hypotheses, the co-creation sessions with student athletes made it possible to test them.

Outcome

The result of our ideation was the following concept:

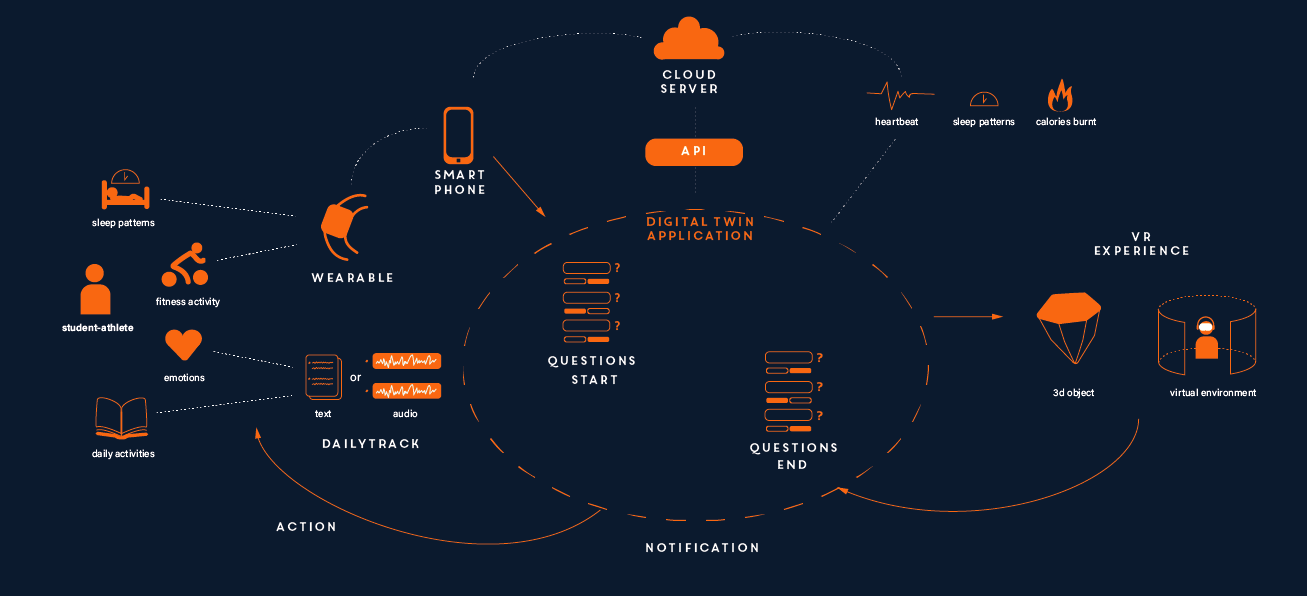

A mobile application with the aim of encouraging student athletes to take a proactive approach to working with their negative emotions. The app collects biometric data of daily energy expenditure, sleep length and blood pressure and combines this data with self-journaling to provide an overview of the experienced emotional states throughout the day.

Our concept scheme

Prototyping and Testing

In Sprint 4 we finally reached the confidence to start rapid prototyping. It was an iterative process, where each new update was based on feedback from user tests.

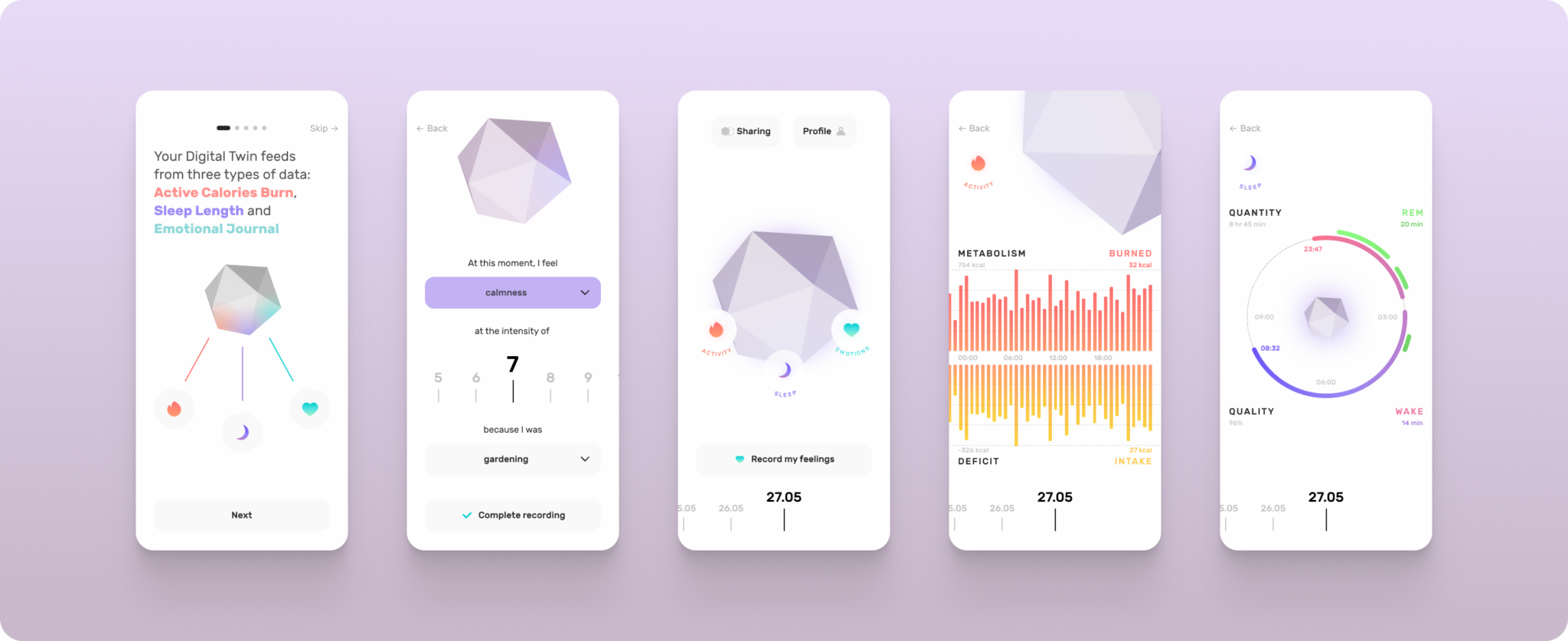

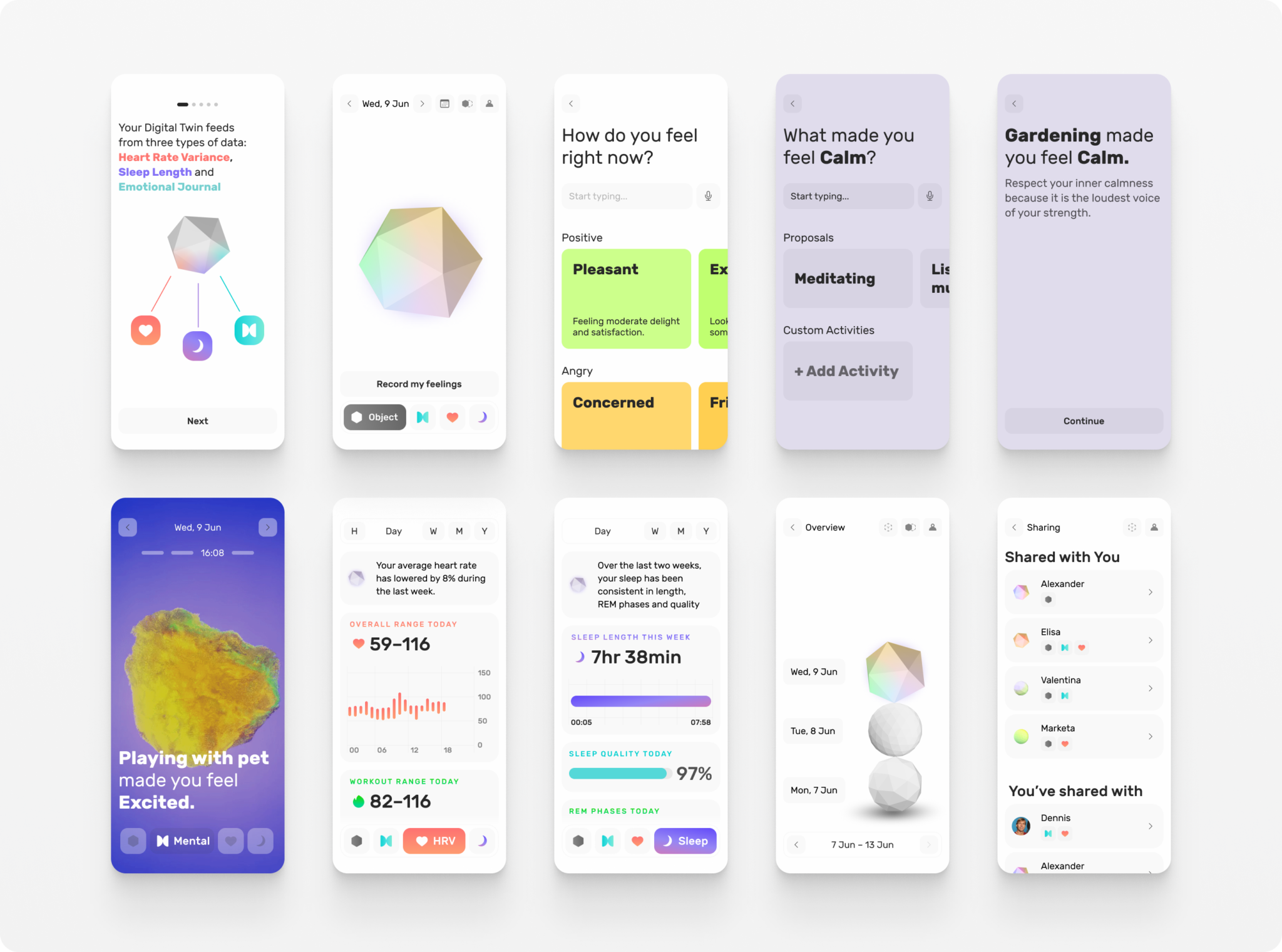

Our first try of the prototype

At the stage of the initial wireframe we tried to lay down the structure of the main parts of the application – onboarding, interaction with a 3D digital twin, recording emotions, viewing data and share mode. We quickly realised that at this stage the user experience was far from the visual and intuitiveness standards we were aiming for, so we put more work in it.

Our second try. Now in light colours!

With the second iteration, we tried to create a more unique look and feel for the app and make it more humane, informative and intuitive. However, it was greatly lacking in accessibility. We devoted too much to the smartphones’ screen reader technology, and missed the fact that the sizes and colours of the elements could have been difficult to use by people with poor vision. Therefore, we went on to improve the prototype in that respect.

The latest version of the prototype

In this, last iteration, we followed the AAA standard of Web Content Accessibility Guidelines for colours and Apple’s Best Accessibility Practices for button sizes and arrangement. With a finalised visual language, improved navigation, and clearer data visualisations, this prototype is now ready to be showcased.