Research

Combating Twitter Harassment with Chatbots

Team Botanic

It was a beautiful September day when we, Olga, Hillary, Maxine and Zahra, started our exciting journey at the Digital Society School in Amsterdam. An affinity for exploring new technologies and a strong desire to make a positive impact in today’s society brought us all together to work on our project.

We found it necessary to talk about an unpleasant, but very important topic: online abuse and harassment. The goal for the first part of our project was to get closer to the problem. We wanted to do so by exploring the problem of online abuse from it’s social, psychological and technological dimensions

Despite not being experts, our diverse interdisciplinary and cultural backgrounds, paired with our desire to create an online safe space propelled us through the investigation phase. The team is very diverse in terms of knowledge and background which we believe will only benefit our project.

Online abuse and harassment

Bullying and harassment is a problem that is likely to affect everyone at some point in life. As internet usage rates continue to grow, social media usage also increased, paving the way for cyber bullying to become a phenomenon. Many studies show that people experience online abuse in different forms and describe it as a frightful experience (Golbeck et al.,2017; Hardaker and McGlashan, 2016). The aftermath of aggression toward victims is also often devastating, and can pose serious health risks such as depression, anxiety, suicide, emotional distress, anger, panic symptoms, lower self-esteem, school truancy, or substance use (Tokunaga, 2010; Sinclair et al., 2012).

Victims of online abuse

For our project we are focusing mainly on the social media platform- Twitter. Twitter is a micro-blogging platform which encourages users to have public conversations and share their thoughts with others. The experience users have on twitter remains mixed, as some groups of people witness a more harmful twitter space than others. In particular many women of color, who are working as journalists experienced the violence and abuse the most. On average, every 30 seconds a woman receives an abusive tweet (Amnesty International Report, 2019).

Why is abuse happening?

It is essential to understand the actual root causes of online abuse. There are several theories which attempt to explain abusers’ behavior. The main idea of Social Learning Theory is that by observing abusive behaviour abusers learn how to be aggressive (Bandura and Walters, 1977). The Cognitive Behavior Theory focuses on the assumptions and interpretations associated with life events and posits that these will be the determinants of abusers behavior. According to the Attribution Theory, an abuser’s perception of others might be exaggerated in it’s hostility, assuming that others are inherently aggressive, which increases the aggressiveness of the abuser. Coercion Theory illustrates that when raising pressure on people is successful, abuse is rewarded which might encourage further abusive behavior (Mishna, 2012).

When dealing with abuse that is happening online, another phenomenon emerges: The Online Disinhibition Effect states that due to missing cues that are usually present during a face-to-face conversation, such as anonymity and lack of facial expression, online dialogue partners are more confident to display atypical and more extreme behaviors than in real life (Suler, 2004).

What can we do?

An effective and increasingly popular approach to interact with online abusers in order to reduce their abusive behavior is counter speech (Schieb and Preuss 2016; Chung, Kuzmenko, Tekiroglu, and Guerini, 2019; Mathew et al. 2019; Munger 2017). In this method, the opponent responds to an abusive comment by following one of several strategies, such as presenting facts to correct misstatements and misperceptions, pointing out hypocrisy and contradictions, or educating them about potential online and offline consequences. Different styles in speech such as positive or negative tone, as well as humor and the usage of image or video messages can support the effectiveness of the counter speech.

How will we do it?

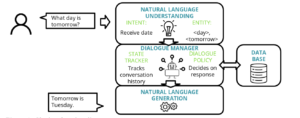

Our chosen method for interacting with online abusers is to deploy a chatbot, or conversational agent. Counter speech is amongst many approaches we can employ to engage with abusers. The identity of the chatbot, it’s engagement style, and it’s choice of diction are all elements we can investigate. On Twitter, this means having an automated system that is able to respond to abusive tweets either by tweeting back at the targeted comment, or by engaging in a private conversation with the detected abuser. Figure 1 illustrates the functionality of such a chatbot when interacting with its user:

Figure 1: Chatbot functionality

What is the benefit of a conversational agent and how can we maximize its potential?

We can point out some key opportunities to justify choosing a conversational AI agent to tackle the complex problem of online harassment. We identified four categories that conversational agents help with: human, technological, health, and social.

Using a chatbot to interact with abusers may be advantageous due to an abuser’s potential response to our bot, and how it may change depending on their ability to identify our agent as a person or a conversation AI. We are not limited by factors that human resources are affected by, such as funding, availability and human error. The technological advantage of our conversational AI is that it should be applicable to any kind of online platform. Regarding health, the chatbot can help abusers to be more aware of their behavior and may lead them to reconsider their behavior, resulting in a healthier online environment.

Last, but not least, are the social benefits of using a conversational agent. Establishing and protecting a safe social media environment is not easy and we should consider the dangers of online abuse seriously. By tackling this problem and creating a more safe social media we can remove the barriers which prevent users from joining the conversation online.

For the development of our conversational agent we will adhere to 5 principles.

- Human centered design. Most chatbots are designed without proper time and expense spent on user testing and this results in a poor user experience.

- Personality. It is crucial for our chatbot to have a personality. During conversation the chatbot should make users feel as if they are talking to a human rather than a chatbot.

- Adaptation. Based on a target group and the goal of the chatbot, it should adapt to the people with whom it is interacting.

- Unstructured conversation. We should be aware of human habits. We do not communicate on Twitter in a structured format and chatbots should be intelligent enough to interact with unstructured conversation.

- Testing. People who are creating chatbots fail most of the time because designers leave the chatbots alone with users after creating it. They are failing because they think their job is done and then they celebrate their work despite the fact that there are many issues with. By analyzing and get more insight from user views and the data from chatbots, you can improve your chatbot and become more successful.

Why should we get involved at all?

A report was recently published by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, which is meant to be used as a practical guide to dealing with hate on social media. The main piece of advice given to combat online harassment is to avoid “feeding the trolls.” For some, this advice works well to preserve a public image, in the case of public figures under scrutiny such as reporters and politicians. There is evidence that self-proclaimed “trolls” are organizing and acting out in order to call attention to themselves or gain notoriety (Center for Countering Digital Hate, 2019), and certainly in this it would be best not to feed the trolls.

However, there is no research to indicate that not feeding the trolls will change their behavior. Trolls are free to continue behaving badly online until someone holds them accountable. There are risks for putting ourselves in the line of fire, because many examples of online abuse are quite nasty. But if we follow this rule, to not feed the trolls, then we are acting as bystanders in a world where people can violate others with impunity. We believe the solution to this problem is a higher standard of behavior online, and the only way to define that standard and to bring online users to the table is to get involved, not to stay silent.

Thanks for reading! If you are interested in this project, feel free to reach out to us and follow live updates on progress on Twitter: @Bot_Botanik

References

Amnesty International (2019). Troll Patrol Findings. Retrieved October 11, 2019, from https://decoders.amnesty.org/projects/troll-patrol/findings.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

Bauer, T., Devrim, E., Glazunov, M., Jaramillo, W. L., Mohan, B., & Spanakis, G. (2019). # MeTooMaastricht: Building a chatbot to assist survivors of sexual harassment. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.02809.

Chatzakou, D., Kourtellis, N., Blackburn, J., De Cristofaro, E., Stringhini, G., & Vakali, A. (2017, April). Measuring# gamergate: A tale of hate, sexism, and bullying. In Proceedings of the 26th international conference on world wide web companion (pp. 1285-1290). International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee.

Center for Countering Digital Hate (2019). Don’t Feed the Trolls. Retrieved October 11, 2019, from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/f4d9b9_ce178075e9654b719ec2b4815290f00f.pdf

Chung, Y. L., Kuzmenko, E., Tekiroglu, S. S., & Guerini, M. (2019, July). CONAN-Counter Narratives through Nichesourcing: a Multilingual Dataset of Responses to Fight Online Hate Speech. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 2819-2829).

Das, S., & Kumar, E. (2018, December). Determining Accuracy of Chatbot by applying Algorithm Design and Defined process. In 2018 4th International Conference on Computing Communication and Automation (ICCCA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Georgescu, A. A. (2018). Chatbots for Education–Trends, Benefits and Challenges. In Conference proceedings of» eLearning and Software for Education «(eLSE) (Vol. 2, No. 14, pp. 195-200). ” Carol I” National Defence University Publishing House.

Golbeck, J., Ashktorab, Z., Banjo, R. O., Berlinger, A., Bhagwan, S., Buntain, C., … & Gunasekaran, R. R. (2017, June). A large labeled corpus for online harassment research. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Web Science Conference (pp. 229-233). ACM.

Hardaker, C., & McGlashan, M. (2016). “Real men don’t hate women”: Twitter rape threats and group identity. Journal of Pragmatics, 91, 80-93.

Hill, J., Ford, W. R., & Farreras, I. G. (2015). Real conversations with artificial intelligence: A comparison between human–human online conversations and human–chatbot conversations. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 245-250.

Katz, S. (2018).Why Chatbots Fail: 5 pitfalls and how to avoid them, chatbotsjournal. Retrieved October 14, 2019, from https://chatbotsjournal.com/why-chatbots-fail-5-causes-and-how-to-prevent-them-178eeca54886.

Lalwani, T., Bhalotia, S., Pal, A., Bisen, S., & Rathod, V. (2018). Implementation of a Chatbot System using AI and NLP. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer Science & Technology (IJIRCST).

Mathew, B., Saha, P., Tharad, H., Rajgaria, S., Singhania, P., Maity, S. K., … & Mukherjee, A. (2019, July). Thou shalt not hate: Countering online hate speech. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 13, No. 01, pp. 369-380).

Mishna, F. (2012). Bullying: A guide to research, intervention, and prevention. OUP USA.

Munger, K. (2017). Tweetment effects on the tweeted: Experimentally reducing racist harassment. Political Behavior, 39(3), 629-649.

Price, R. (2016). Microsoft is deleting its AI chatbot’s incredibly racist tweets. Business Insider.

Schieb, C., & Preuss, M. (2016). Governing hate speech by means of counterspeech on Facebook. In 66th ica annual conference, at fukuoka, japan (pp. 1-23).

Shawar, B. A., & Atwell, E. (2007, January). Chatbots: are they really useful?. In Ldv forum (Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 29-49).

Sinclair, K. O., Bauman, S., Poteat, V. P., Koenig, B., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Cyber and bias-based harassment: Associations with academic, substance use, and mental health problems. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(5), 521-523.

Skjuve, M., & Brandzaeg, P. B. (2018, October). Measuring User Experience in Chatbots: An Approach to Interpersonal Communication Competence. In International Conference on Internet Science (pp. 113-120). Springer, Cham.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & behavior, 7(3), 321-326.

Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in human behavior, 26(3), 277-287.

van Rijmenam, M., Schweitzer, J., & Williams, M. A. Overcoming principal-agent problems when dealing with artificial agents: Lessons for governance from a conversation with Tay.